xxx A multi-faceted life:

A profile of Dieter Koschek of Wasserburg

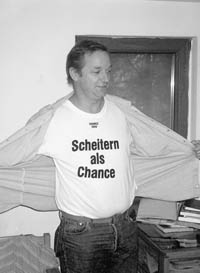

So what possible ways are there, in our society, of reconciling these external demands in our daily lives with our personal expectations (or even our desires)? In this article I'm going to describe a way that has already been forged, and is available to those in reasonably good health and with a willingness and ability to work. This is a profile of Dieter Koschek and the Modell Wasserburg e.V. project on Lake Constance in southern Germany, and the harmonizing of the different spheres of life. It is the story of an alternative project which, after much change, has now arrived in the third millennium; the story of Dieter Koschek's activism and of social and political events in Germany and its regions. It's about the threading together of diverse activities into a rich tapestry, and an attempt to live a life as textured and complete as the work of the artist Beuys. Dieter Koschek is, along with many of us, a child of the seventies. He studied social work and was involved in socio-political initiatives, commencing his professional life in a youth centre. The multiple skills he gained there have been much used, and are his 'qualifications' for keeping on top of his current strenuous existence, and for being able to continually push himself further. For many, the 'seventies was just an era, but for him it was a starting point. The most important event was

when he joined, and began working with, the Modell Wasserburg project at the end of the

'eighties. The project describes itself thus: 'In 1976, Peter Schillings founded an

association named the Modell Wasserburg e.V. with some friends, which was to provide the

legal framework for the founding of the Eulenspiegel project: a cultural centre based on

Rudolf Steiner's philosophy. The restaurant and bar were not to be privately owned by one

individual but by the association, offering a home and a living to those who wanted to

work in the context of this ideal. The setting-up of the project was made possible by old

and new friends supporting the idea with donations and loans, which provided a large part

of the finance to buy the building. Steiner's philosophy contains the idea that society's

development requires separate consideration of culture, public life and the economy,

because each of these sectors has different development needs. For culture in particular

(art, education, science etc.), an openness to all viewpoints is essential.' An idyll? Being a product of the 'alternative movement', the project has been through its ups and downs. There were lots of people who got involved, stayed for a longer or shorter period, then left again. Today the Modell Wasserburg e.V., with the restaurant as its income source, has four permanent employees plus further helpers. Dieter Koschek explains how the current situation evolved: 'For some time, the association 'owned' the restaurant, on the principle that no individual should even nominally have the role of manager, tenant or proprietor. But this model didn't work in the end. It started with small details, like who had access to the bank account. Then there started to be a separation between those who worked in the restaurant and the members of the association, who in general didn't work in the restaurant. Being active in the association was never a condition for working in the restaurant, and some restaurant workers just didn't want much to do with the association. The day came when the board of the association consisted solely of people who didn't actually work in the project. Hence the idea was born of employees 'leasing' the restaurant. But just as this decision was made, something strange happened: the group started to dissolve. Inter-personal conflicts meant that one person had to leave. I myself moved in with my girlfriend; another woman moved closer to her children; someone else left for Greece; another became ill - and suddenly everyone was gone. The two remaining workers didn't feel in a position to carry on with the restaurant, and this was the moment when I stepped in.' Since the beginning of 2001, Dieter Koschek has been the leaseholder of the restaurant: 'It's difficult working with a group on a commercial basis. There are several models and forms in Germany but nothing that suits a true 'joint enterprise'. It's difficult, quite simply, to manage and develop a company as a group; to open up commercial opportunities and develop one's own product.' He explains the reasons for

this as follows: 'Everyone's different. Whenever anyone made a suggestion, a long

discussion followed, and in most cases there would be someone or other who would oppose

it, either because it didn't feel right, or it meant more work, or he/she wasn't sure

whether it would work. In a group, everything happens much more slowly.' Dieter Koschek sees the work

of the Gaststaette Eulenspiegel as part of a range of activities. Eulenspiegel is also a

venue for the region. Every Thursday there is a discussion group dealing with topics from

'the marketing of organic products' or Steiner's 'threefold social order' or just an open

forum. It's the building itself which, for Koschek, makes all these activities possible,

from the discussion group to the editing of the magazine Jedermensch (in print for over 40

years), to the management by volunteers of the AG SPAK publishing house. 'When you really look at it, we aren't just another business. We're still a social experiment, where new ideas are being put to the test. For me, the Eulenspiegel is still a model project in the context of the alternative economy, with a different approach and attitude to people. We have attractive living spaces, a pleasant atmosphere and possibilities for political activism and involvement in all kinds of things.' Dieter Koschek has created a multi-faceted daily life for himself which isn't always devoid of conflict, but which is possible due to the structure of Modell Wasserburg. He describes the on-going learning process and conflicts within the group; his business activities relating to the restaurant to make it financially secure; and his relationship. His ideals, his working life, and the demands of a wife and child have all to be taken into account and integrated in daily life. 'I live in a house owned by the bank, self-built according to ecological standards.' His many activities focus ultimately on social relationships, on affirmation or rejection, and on the living-out of one's ideals. That's not all there is to life, but it's a starting point, and is the result of his attempt to take control of his own life. And this is a privilege in society, even though there's no guarantee that everything will work out according to plan. The only guarantee is that everything will work out somehow in the end! It's a 'give and take' situation: the 'giving' dimension is evident in so many activities: the social security initiative in Lindau; the campaigning for subsistence payments by AG SPAK; the Gaststaette Eulenspiegel's ecological concerns, and sharing in bringing up Oskar. The 'taking' dimension is in things such as a holiday in the Case Coro Carrubo conference centre in Comiso, Sicily, financially supported by Modell Wasserburg. A holiday there is so much more comfortable and personal; friendships are maintained, and, almost incidentally, social and ecological aims become integral to daily life.

|

|||

|

Email:

Waldemar Schindowskii |

||

| LINK

TO: Modell Eulenspiegel: www.eulenspiegel-wasserburg.de |

|||

| | TOP | PRINT THIS PAGE | | |||

There are enough

potted biographies and enough publications on new forms of work, the relationship between

work and family, and the new self-employed, to fill entire bookcases. I would like to

suggest here that most of the authors are people who take part in panel discussions but

have no personal involvement with their subject-matter. Having said that, their

publications no doubt contain a kernel of truth. Nearly everyone thinks and feels that

social circumstances are changing, be they in the workplace, gender relations, the need

for qualifications, or the new self-assertiveness. People are responding to these changes

in different ways: some are anxiously fighting them off; others are putting on a benign

('neo-liberal') expression and going around saying everything's fine.

There are enough

potted biographies and enough publications on new forms of work, the relationship between

work and family, and the new self-employed, to fill entire bookcases. I would like to

suggest here that most of the authors are people who take part in panel discussions but

have no personal involvement with their subject-matter. Having said that, their

publications no doubt contain a kernel of truth. Nearly everyone thinks and feels that

social circumstances are changing, be they in the workplace, gender relations, the need

for qualifications, or the new self-assertiveness. People are responding to these changes

in different ways: some are anxiously fighting them off; others are putting on a benign

('neo-liberal') expression and going around saying everything's fine.